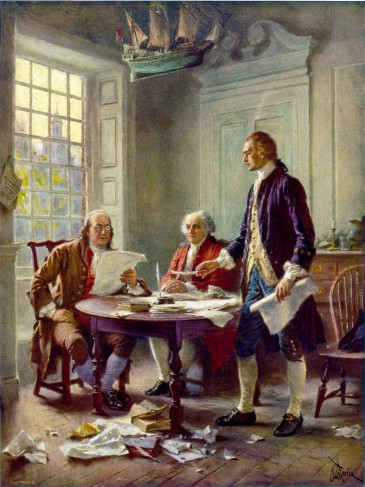

Leaving a Legacy – 18th Century Style

Two American Revolutionaries struggled to tear the Colonies away from British rule, now they are known for their words—not their swords.

John Adams, a short, cranky, pudgy Yankee, swung the First Continental Congress with his intellect and the strength of his common-sense arguments. At 41, Adams, who headed the committee tasked with writing the Declaration of Independence. disrupted his standing and upended his own legacy when he plucked 33-year-old tall, suave, handsome, popular Jefferson of the golden pen from the steno pool (not exactly, but in 1776 the two men operated from entirely different political spheres.) Defining characteristics come from historian David McCullough, whose spent a lifetime “knowing” these two, in part because he got to read their mail.

Adams’ diary tells us the Second President could only start to think when “I sit down at the desk with a piece of paper and my pen.” Thinking being an art in short supply then and even less today. Modern political leaders and writers receive their training from diverse institutions and (hopefully) read from a myriad of books and materials. The Founding Fathers all were familiar with Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”: “Act well your part, there all the honor lies.” Honor seems not to be the goal sought by the combined leadership in 2021, more is the pity.

Ironic for a Harvard man and respected lawyer, Adams grew up one of three sons in an impoverished household that owned a single book, the Bible. His mother was illiterate; his father a small-time farmer and preacher, who brought John along when he moderated town meetings, inspiring his son’s interest in community affairs. Seeking to fulfill his desire that his son go to Harvard, Deacon Adams sold a portion of his precious family land. The payoff? Junior discovered books and bragged “I read forever,” giving a foundation to his purpose in life. From this knowledge grew the man whose words swayed the Colonist legislators to stand up to the British and stay the course for seven long, brutal years.

A little Adams bio could aid those who did not dip into McCullouch’s superb take on him. Before he began his political career, he rode the court circuit in Massachusetts, just as Abraham Lincoln did in Illinois. Few remember the principled role Adams played after the Boston Massacre. No American lawyer would stand up to offer legal services to British soldiers charged with the death of Americans. Adams feared that offering legal aid to the British soldiers could destroy his future legal and political career, but Adams took on the case. He said: “If we believe in what we say, somebody’s got to represent them. If you all will not, I will.”

Instead of sinking his career, the trial brought Adams more popularity after doing what he believed to be right. Adams won election to the Massachusetts Legislature. He did not just take on the Brit’s case on American soil, he proved to the jury that the soldiers were performing their military duty, protecting themselves, acting in self-defense against the mob, without intent to murder. But he remained an ardent critic of Great Britain’s policies.

Adams took another stand unpopular among the landed gentry north and south. He and wife Abigail stood together in their opposition to slavery. Adams became the only signer of the Declaration of Independence to take that stand. In a letter to Abigail after the Continental Congress voted on July 2, 1776: “This will be the most important day in the history of our country.”

Adams grew to regret his selection of Jefferson to write the Declaration. Not because he was not talented, but Adams felt bruised and brushed aside as the spotlight shifted to the younger man who received full credit for the Declaration, despite Adams’ leadership and committee review after the initial draft. Successful passage of the Declaration and the necessary signatures depended on Adams’ oratory that pulled legislators on board[ME1] .

As the Revolutionary War wound down, Adams retired to Braintree, Massachusetts, then served as a Joint Commissioner to negotiate for Peace with Great Britain, then served on a diplomatic mission to France. Adams compensated for his lack of French language skills by studying on board ship crossing the Atlantic. He reviewed and signed the Treaty of Paris, securing recognition of the United States’ independence from Great Britain.

Later lanky, diplomatic, wine connoisseur, and multi-linguist Jefferson traveled to France to replace Adams as envoi. He served as Adams’ vice president based on the number of votes he received in an era when the President and Vice President were not always of the same political party. Four years later in 1800, Jefferson turned the tables and beat Adams for the Presidency.

Adams can be forgiven for being cranky that as the U.S.’s Second President he did not receive the public adulation of his successor.[ME2] The two men had one official sit-down, when Jefferson served as his VP. The relationship did not go well because they did not pencil in regular lunch dates, but more likely because they came from different sides of the political spectrum.

Few Presidents have failed to accompany their successor to their inauguration, most recent excepted. But John Adams ducked out of DC before Jefferson’s swearing in. While some saw this as the ultimate snub, they did not know the entire story. Adams had rushed home to Massachusetts to Abigail after the death of their son, Charles. Their son’s alcoholism caught up with him. Not information one would broadcast in 1801. His eldest son, John Quincy became an avid reader like his father and accompanied him when he served in Europe, learning the ropes. Eventually he himself served as an American statesman in the 1780s, and subsequently won the White House—a legacy repeated by few others.

If this tickles your fancy to learn more about the Founders, peek into The American Story, Conversations with Master Historians, a 2019 book by David M. Rubenstein featuring interviews with prominent historians, like David McCullough, Jon Meacham, Ron Chernow, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Tyler Branch and Robert Cairo. Or check out McCullough’s John Adams.